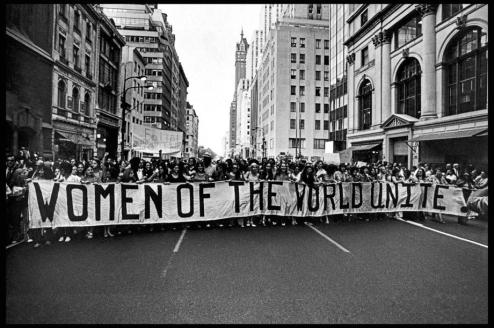

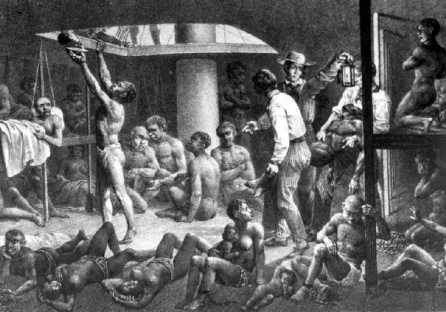

Calvino’s “exactitude” (or “exact”) appears in literature in the form of mood, atmosphere, and general tone. Already we’ve seen that The Invention Of Wings is full to the brim with emotions on both sides of the playing field: a trapped and (constantly) endangered slave, Hetti, and her mother, Charlotte — both discriminated against, dehumanized, controlled, manipulated, outcasted, harmed, and mistreated, THE LIST GOES ON; and then we have the white plantation mistress’s daughter, Sarah, and, though born into privilege on the mere basis of being white-skinned, she doesn’t tolerate slavery in the least bit and goes on to dedicate her life to the anti-slavery cause while concurrently fighting for the rights of women. Both are members of womanhood, and in that perspective they are two sides of the same coin — Sarah’s side being ten tiers above Hetti’s. Both are discriminated against and made inferior on the basis of being women. In Hetti’s case, she is not only suppressed as a woman, but is also considered to be less than a human due to the pigmentation of her skin.

Calvino’s “exactitude” (or “exact”) appears in literature in the form of mood, atmosphere, and general tone. Already we’ve seen that The Invention Of Wings is full to the brim with emotions on both sides of the playing field: a trapped and (constantly) endangered slave, Hetti, and her mother, Charlotte — both discriminated against, dehumanized, controlled, manipulated, outcasted, harmed, and mistreated, THE LIST GOES ON; and then we have the white plantation mistress’s daughter, Sarah, and, though born into privilege on the mere basis of being white-skinned, she doesn’t tolerate slavery in the least bit and goes on to dedicate her life to the anti-slavery cause while concurrently fighting for the rights of women. Both are members of womanhood, and in that perspective they are two sides of the same coin — Sarah’s side being ten tiers above Hetti’s. Both are discriminated against and made inferior on the basis of being women. In Hetti’s case, she is not only suppressed as a woman, but is also considered to be less than a human due to the pigmentation of her skin.

Searching for an excerpt that accurately expresses the overall tone and mood of the novel, I came across the scene where Hetti’s mother, after all her life of slaving away, is finally laid at rest (narrated by Hetti herself):

“‘Mauma?’

She lifted her face. The light had gone from her eyes. There was only the black wick now.

I eased down beside her. ‘Mauma?’

‘It’s all right. I come to get my spirit to take with me.’ Her voice sounded far off inside her. ‘I’m tired, Handful.’

I tried not to be scared. ‘I’ll take care of you. Don’t worry, we’ll get you some rest.’

She smiled the saddest smile, letting me know she’d get her rest, but not the kind I hoped. I took hold of her hands. They were ice cold. Little bird bones.

She said it again. ‘I’m tired.’

She wanted me to tell her it was all right, to get her spirit and go on, but I couldn’t say it. I told her, ‘Course, you’re tired. You worked hard your whole life. That’s all you did was work.’

‘Don’t you remember me for that. Don’t you remember I’m a slave and work hard. When you think of me, you say, she never did belong to those people. She never belonged to nobody but herself.’

She closed her eyes. ‘You remember that.’

‘I will, mauma.’

I pulled the quilt round her shoulders. High in the limbs, the crows cawed. The doves moaned. The wind bent down to lift her to the sky” (303-304).

Making this moment even sadder is the fact that Hetti’s mother had only recently returned back to the plantation after having been gone for thirty-some years — gone from her daughter’s life ever since Hetty was just a teenager. The part where her mother tells her, “When you think of me, you say, she never did belong to those people. She never belonged to nobody but herself” (304) — is especially important because it is her mother’s last wish; she wants her daughter to have the best vision of her possible, to see her for her strength and willpower rather than for her suffering. Charlotte lived her whole life being owned by others, like chattel, like property. Her only means of escaping slavery now becomes death. The white slave owners may “own” her body but they cannot entrap her soul and spirit — a fact that Charlotte, Hetti’s mother, proves even before her death via her little — albeit persistent — instances of rebellion. This whole novel is then a remark on slavery, oppression, and civil rights, and is an accurate depiction of the myriad feelings possessed by slaves and black Americans at the time and that went overlooked altogether.